Get In Touch

hello@untangld.co

Get In Touch

hello@untangld.co

Follow

|

LinkedIn

We use cookies to make sure you have the best experience on our website. Fear not, we don’t sell your data to third parties.

That an abundance of customer research, data and clever people around a table can predict the future. If we have been reminded of anything in the last few years, it’s that we are the future’s bitch.

When everyone sits back, nods along and says at the end, ‘that makes sense’, you can be confident bad strategy has been presented.

Bad strategy wades in shallow waters, helping people take a few steps forwards while trying to avoid seaweed and jellyfish. But that’s not where the real sharks live.

The best strategies shed light on the opportunities hidden in unfamiliar places. The best strategies help us unlock the audiences we didn’t know existed. The regions we don’t understand. The products people didn’t know they needed. These are the strategies that unlock new feelings and unexplored associations that help businesses and brands create disproportionate impact.

But here’s the catch. Being evidence-led (which we should all be) in unexplored territories is inefficient. It’s not a linear process. It forces us to be lateral thinkers.

Inefficiency gets a bad rap. It’s associated with laziness, thoughtlessness, and poor organisation. But that’s not completely true. Inefficiency is exploration and creativity. It can be effective. It depends on how businesses institutionalise healthy inefficiency.

Fail fast is a great example of that. Developing inefficient yet effective strategies demands selling boards on uncertainty. And that’s pretty damn hard.

That’s the skill of a great strategist. Present the facts in such a way that invites really smart people to tackle the unknown path because it’s more attractive than the known. Uncover the evidence to inspire a moon shot.

This is true for all types of strategy. Business, experience or creative.

Don’t get me wrong. This isn’t about guessing or intuition. This isn’t about using 30 years of experience as an excuse for not investing in research.

In fact, according to Ritson, if you’re not investing 5% of your budget on research, you don’t know what you’re doing. I would even go further. Invest in better research. Most research is useless, because it asks the wrong questions. It asks the questions everybody is asking and all you’re doing is levelling the playing field.

There’s data everybody either has (thank you Google) or pays for via table stakes research (Think Mintel or basic research studies). This is where every good strategy starts. Sadly, it’s where most finish.

But it is almost impossible to invite smart people who live and breathe a business to open their minds to new opportunities if you don’t bring something new to the table.

If the data doesn’t get people asking, “if that, then maybe…”

The two questions you’ll almost always get are the same. Is the data believable and why hasn’t anyone else done something with this?

The privileged insight is the start of the conversation. Not the end.

If you’re truly looking for answers in uncomfortable places, you need to be clear what’s at stake. Why is the effort and risk worth it?

This isn’t some generic dollar figure about how much an audience or category is worth. We’ve all read an IBIS report. Market size isn’t the same thing as your opportunity. The opportunity should feel somewhat unique. Great strategy creates a sense this opportunity is ours to take.

It’s tapping into a new market or audience. It’s unlocking a new behaviour or unlocking hidden value in the product. It’s any or all of these with a direct line to commercial impact.

Uncomfortable places are made more familiar with company.

And although you probably shouldn’t be able to find anyone that’s done it before in your category, you can find examples further abroad that support the hypothesis.

And if you’re truly a first mover and building reusable rockets to get us to Mars, then what you need isn’t references but prototypes. Invent, test and evolve.

Ultimately, this is about using better, different evidence so you can make better, different decisions.

This is about getting comfortable running in the dark.

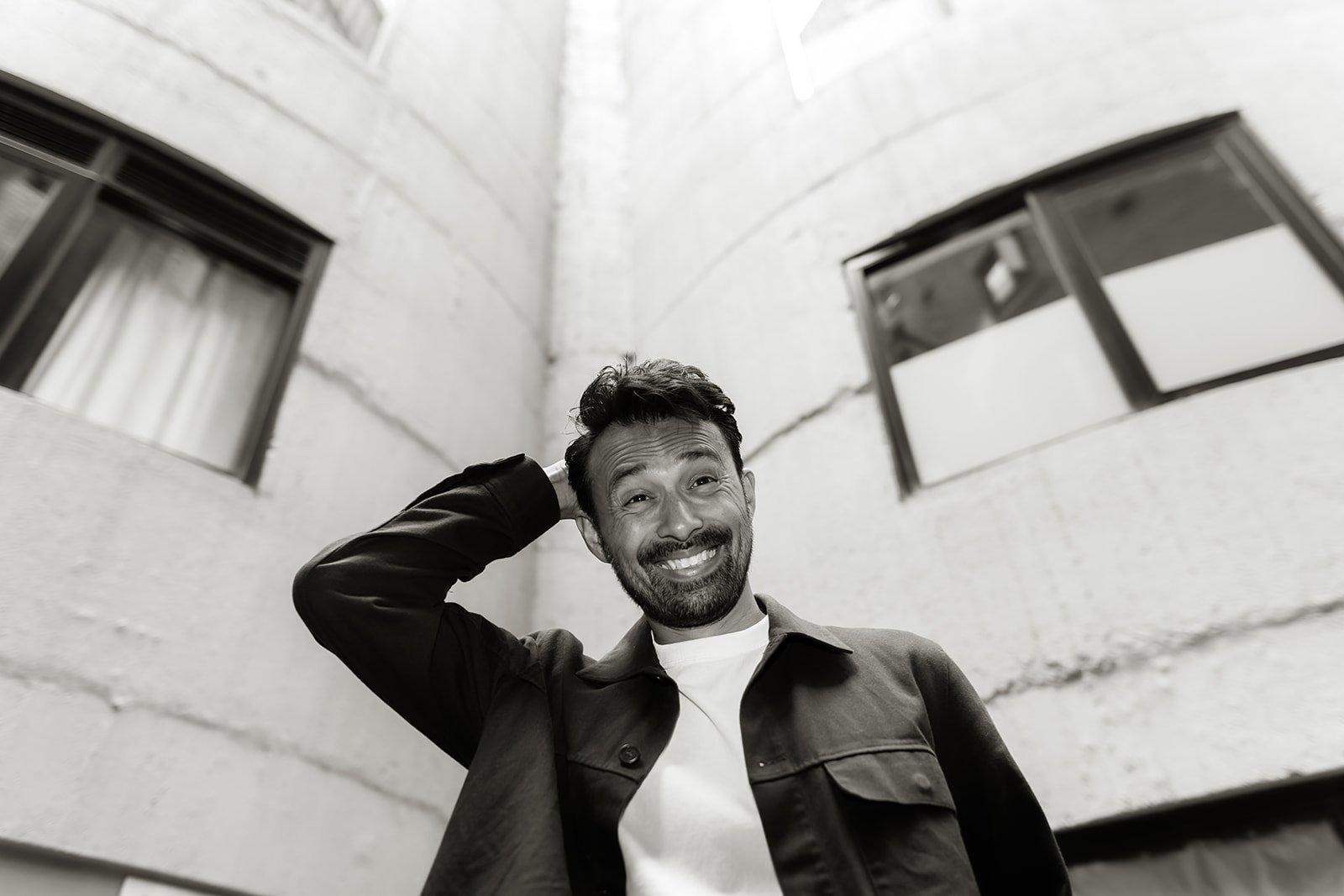

→ Danish is one of the most awarded strategists in the world, having worked on some of the most iconic brands in the last decade including Virgin Atlantic, Coca Cola, and Volvo. Danish spent his career helping to make modern, connected strategy integral to world-class effective work. A co-founder of Untangld, and a founding partner of By The Network, Danish is also a regular judge at the Effies and WARC Global Effectiveness Awards and a contributor to popular industry rags.